Prospect Sierra

“I’m not a math guy…” and other explorations around student identity with STEM

Oftentimes in the design process, coming up with a “point of view” to guide design is challenging. However, focussing on a point of view allows designers to flare and come up with novel ideas to innovative. We spent time with the team at Prospect Sierra drilling to, defining and redefining their point of view of the intersection of STEM and empathy and why that mattered for them personally and for their school.

Starting with a STEMpathy Manifesto

Before we arrived for our design day, we had the Prospect Sierra team write their own STEM and empathy manifestos so that their thoughts and opinions on the subject were documented. Each educator brought a diverse perspective -- in the room we had the Director of Technology and Innovation for the school, Director of Diversity, the elementary co-lab teacher (an experimental maker lab for students), and the librarian. We used the following guide to create manifestos:

I believe ___(your take on STEM and empathy)_____ because ___(why it is needed)_____.

______(what inspires or bugs you about the topic)_______ drives me to do / or question ________. Therefore, we should dig deeper into ______(what area this makes you want to explore further)__.

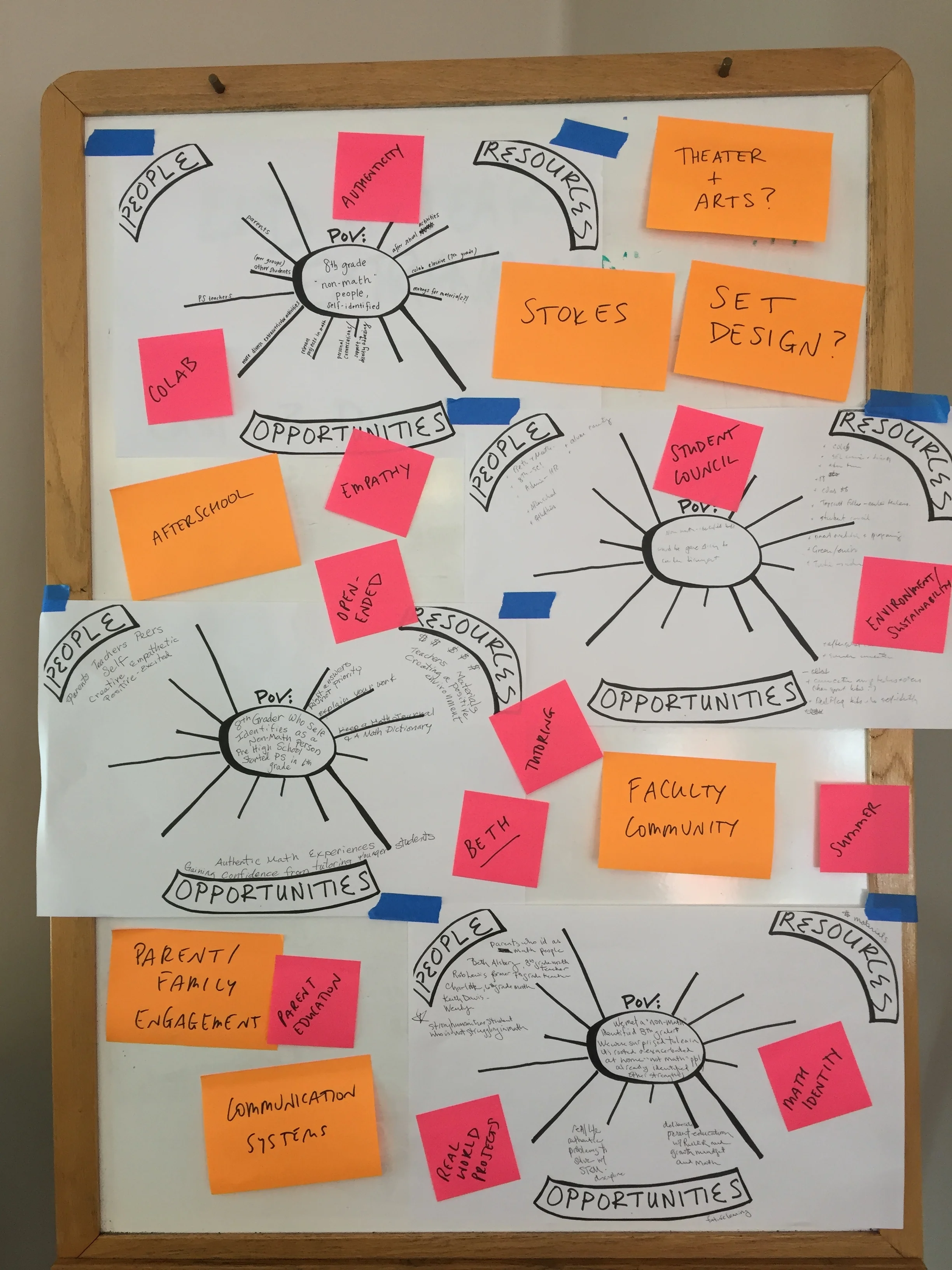

As designers, our own personal bias and stories can often disguise the needs of our users, so we wanted to make sure to have the team articulate what stake they have in the challenge area in order to test their assumptions. After doing some of our own observation and empathy work, we also wanted the team to map out all the possible people, resources, and opportunities they had around them, working in their favor, and any pitfalls they might face.

Design On!

We kicked off the design day with some energy and inspiration. We heard from Alissa Murphy, our colleague at the d.school, who is an engineer. She spoke about her journey in discovering her interests and how that was and was not supported by family, friends, and school. She noted how, growing up, it was always very obvious whose parents were doctors or lawyers or teachers, but there were very few engineers, let alone female engineers to talk to. And when engineering was visible to her, it often looked like building cars. Alissa helped set the tone for exploring how STEM is perceived and how students access it and define themselves by their passions and by school subjects.

Sometimes More Empathy is Needed

All the educators came to the design day not only with their own point of view (POV), but with POVs generated from talking with a teacher or observing a classroom that either was successful in teaching STEM or not as successful. We mapped all of the team members’ points of views out and selected one to refine and use as a starting point for design. Some of them starting wondering, “I wish we could ask this student whether or not they feel like they are a ‘math person’ and why…” so, we pivoted! We paused the agenda to interview students in real time on how they feel about the STEM subjects and STEM as a potential career path. We came back with profound statements from Kobe and Emily, unearthing some of their passions in and out of school that weren’t necessarily visible on the day to day -- and how those outside passions fed into their identity and motivation to pursue a future in STEM. With all this new information, we generated our final POV for design:

We met Emily and Kobe, two students who question whether or not they are “math people” because they self define as more of a 1) kinetic learner who can see the connections from class and be participatory in her own learning and 2) humanities and science person. We were surprised to realize that both had a serious and sustained interests completely outside of school. It would be game changing if students like Emily and Kobe could leverage their outside passion and see the connections and relevance to their in-school learning journey and identity formation.

A New Point of View in an Existing Environment

We knew we had to call attention to the resources Prospect Sierra schools already had in their favor. And so, we made simple mind maps, which you can see in our resource section for the day that detailed --

PEOPLE (Who is meeting this need already?)

RESOURCES (What do we have to use to meet the need?)

OPPORTUNITIES (Where are there potential opportunities for us?)

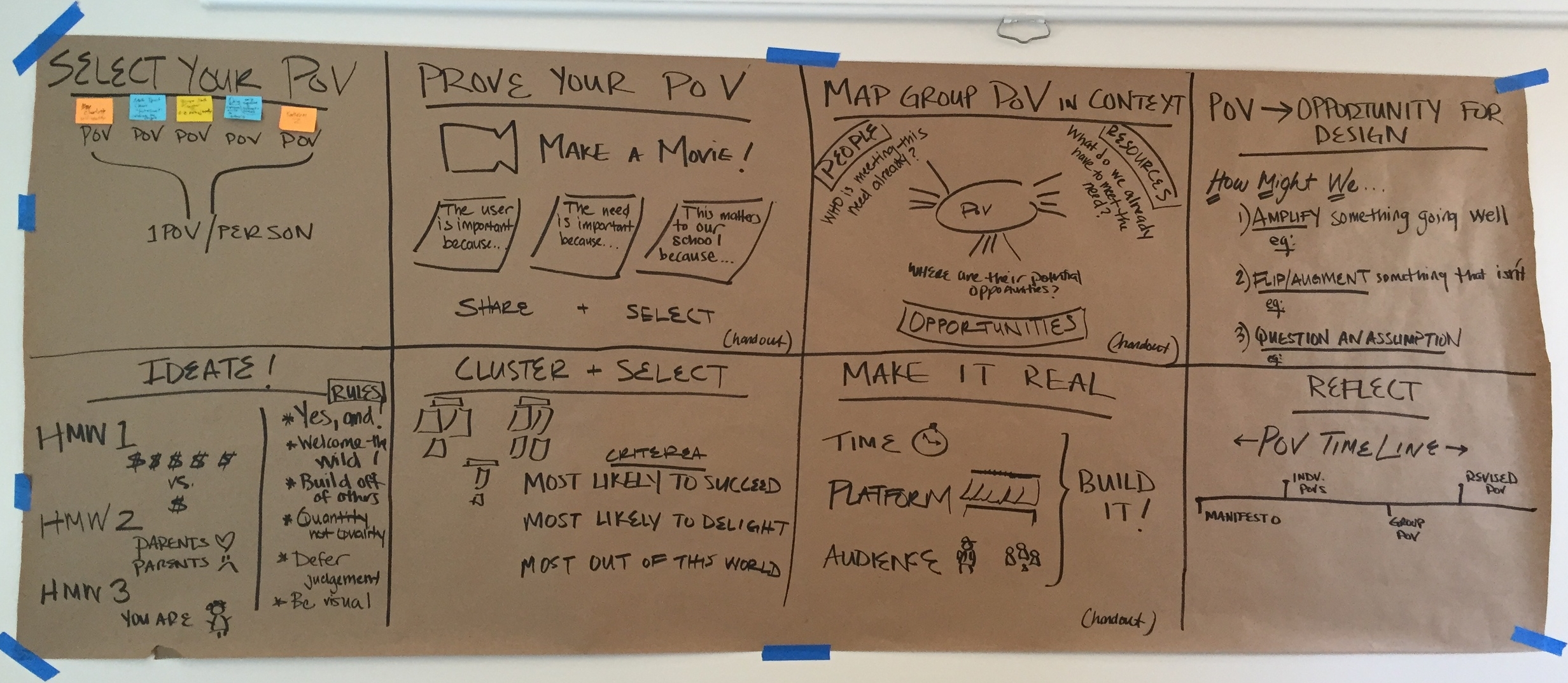

With our POV in Prospect Sierra’s context to guide our path, we launched as a team back into a more traditional design process. From this POV, we crafted three How Might We Statements to start the brainstorming phase.

- How might we help students connect their outside world to their learning?

- How might we leverage the energy from the elementary Co Lab to re-inspire middle schoolers to be STEM thinkers?

- How might we create new ideas of STEM-identities?

Ideas, Themes, Levers....Prototypes!

We generated ideas on all three How Might We statements, combined and sorted them into emerging themes like Peer Teaching, Assessment, Mentorship, Redefining STEM, External Partnerships and more. Each educator sticker-voted by selecting one idea that was most likely to succeed, one most likely to delight, and one that was most out of this world.

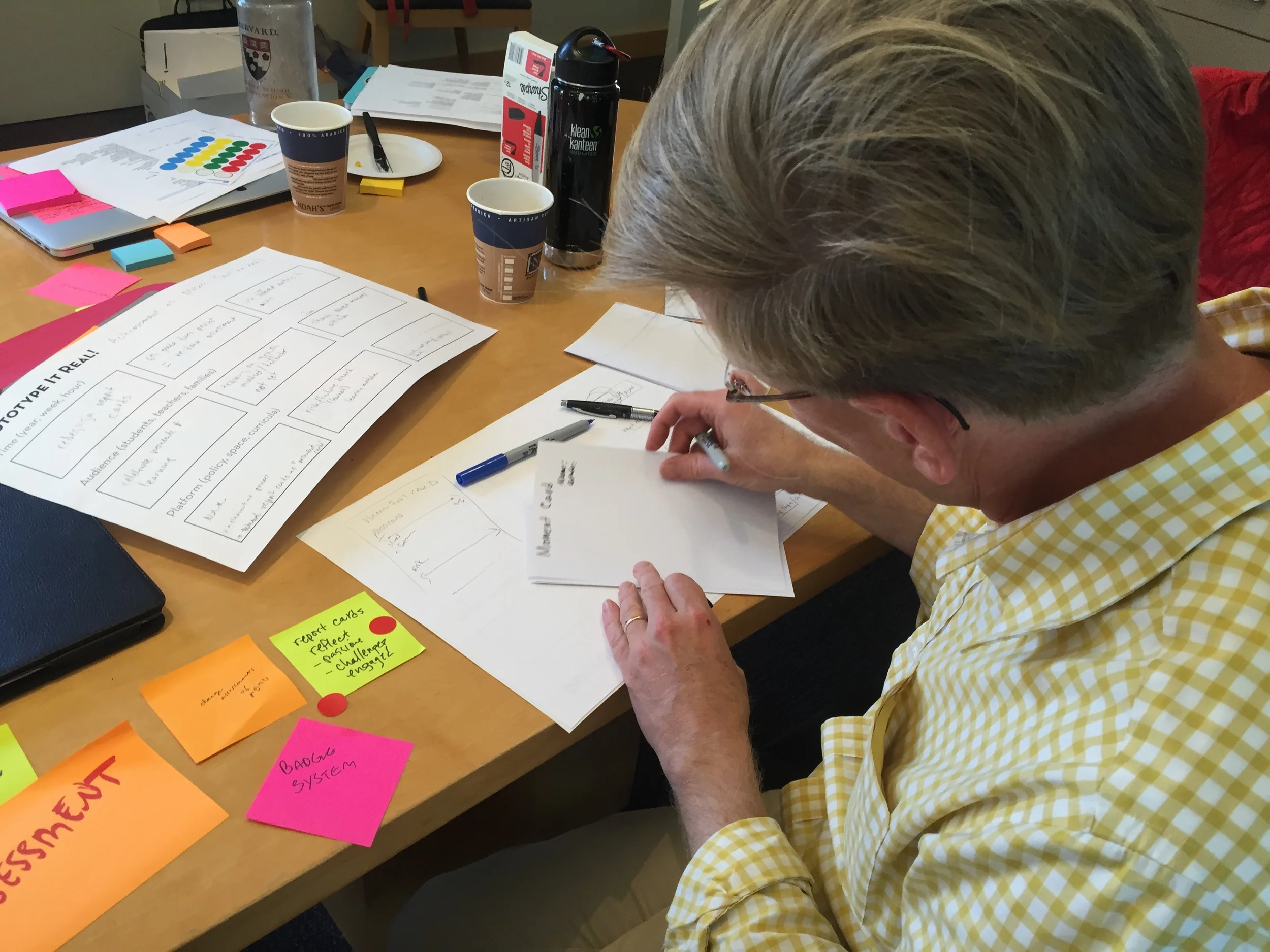

To bridge the gap between idea and prototype, we played with levers as we have done in many of our workshops. This time we broke up different levers of designing prototypes by Time, Platform, and Audience. Each educator filled out a few concepts for each (what might this idea look like in the frame of a week, month, year? As a space? Campaign? For students? Parents? etc.)

From that we brought two ideas to life, combining one time frame, platform and audience together to create each full prototype concept. One prototype was the “Moment Card,” an addendum to the report card with a Passion and Bravery index. The other was a weekly “Unlikely Mentors in STEM” speaker series where students ask the questions to a panel of diverse professionals. Our team ran out to test the the Moment Card and mentorship series with other educators and students and got quick feedback, which, as it often does, generated more questions and more assumptions to keep testing.

In closing

The reflection of the day centered around generating a final point of view based on their learning journey from the day, especially reflecting back on their original, individual manifestos on the importance of STEM and empathy. In design, we often see new insights completely changing thought patterns or flipping our original assumptions, but we also see new insights confirming original hunches and assumptions. As the educators looked back at their original manifestos, written before they did any empathy work, interviews and observations, they saw that their point of view didn’t necessarily change, but was heightened and now supported by real stories and surfaced more questions for the future. The next steps emerged: talking to students all over again -- and so the design process becomes a circle. We left our visual agenda and other artifacts in the conference room for other teachers to see in hopes of gaining more school wide support for the wonderful work of the d.home team educators at Prospect Sierra.