Mindsets into Action

During the fourth session with District 11 in Colorado Springs, we focused on perceived constraints in our environment and how to shift mindsets. We started the day with a discussion around the “Broken Escalator Theory”: A broken escalator is just a set of stairs but if we fixate on the fact that it is not functioning like an escalator anymore we can lose site of the fact that it can still meet our needs just not in the way we imagine. We used this as a metaphor for the challenges that educators face at their own schools. What are challenges we perceive as insurmountable that may look as simple as a broken escalator to someone from a different perspective? This led to a great discussion around the assumptions we make about school.

Talk, talk, talk…

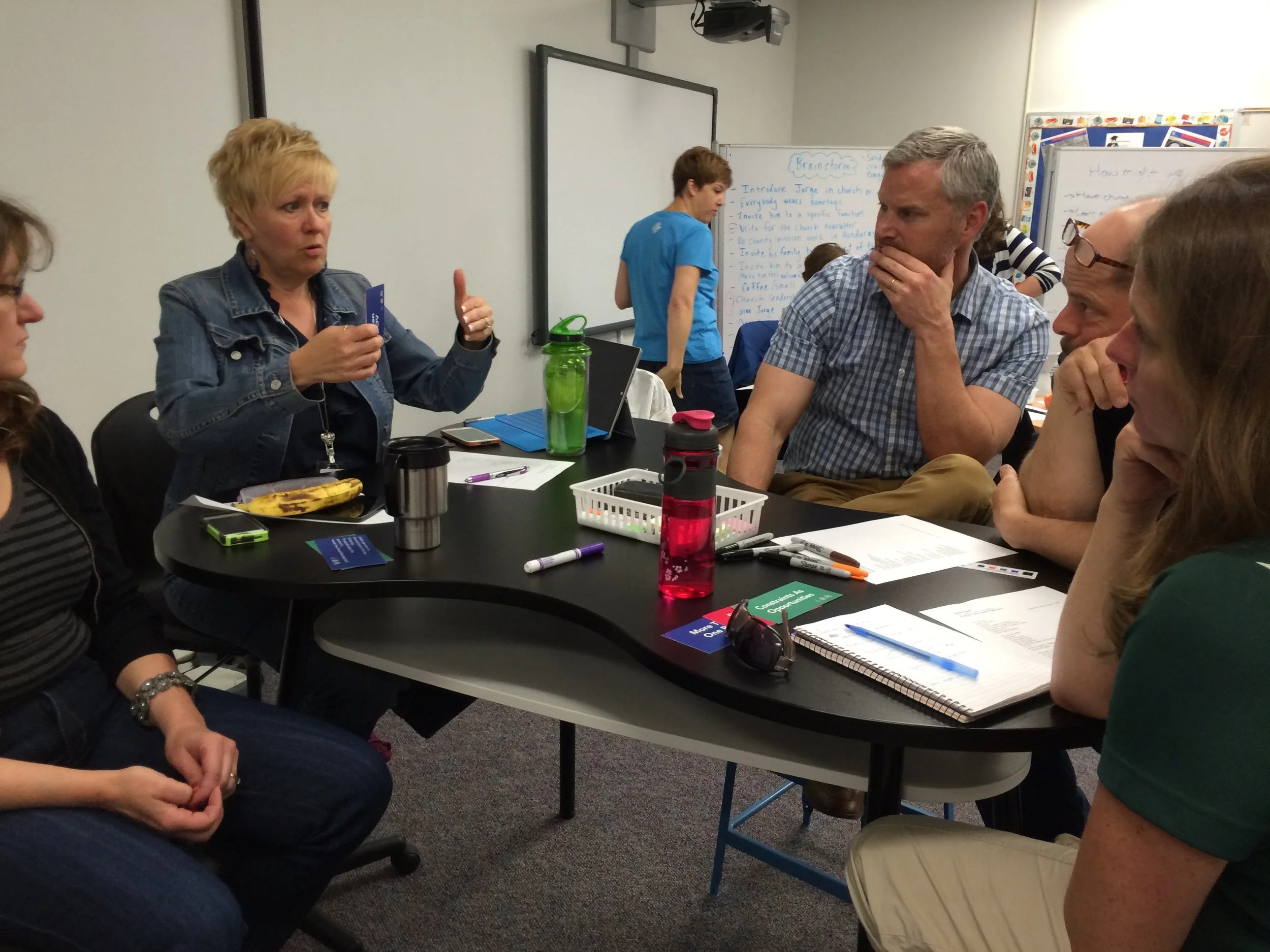

One constraint many educators deal with is communication style. We dove deeper into this perceived constraint with an activity called “Talkers & Listeners” in which participants self-identified as talkers or listeners. The activity sparked a lively discussion. The team discussed the value of “Talkers and Listeners” as a tool for differentiation in the classroom.

Adapt it:

Our educators realized that taking an approach in which they recognized and worked with the many different communication styles that exist just as they work with the many different learning styles could help them break through many perceived constraints. They saw many applications for this, including: a tool to increase empathy, a tool to better accommodate different learning and communication styles, and a tool for reaching ESL students or other students who have challenges with verbal communication. Our educators left feeling empowered to break down many barriers.

Literary Likeness

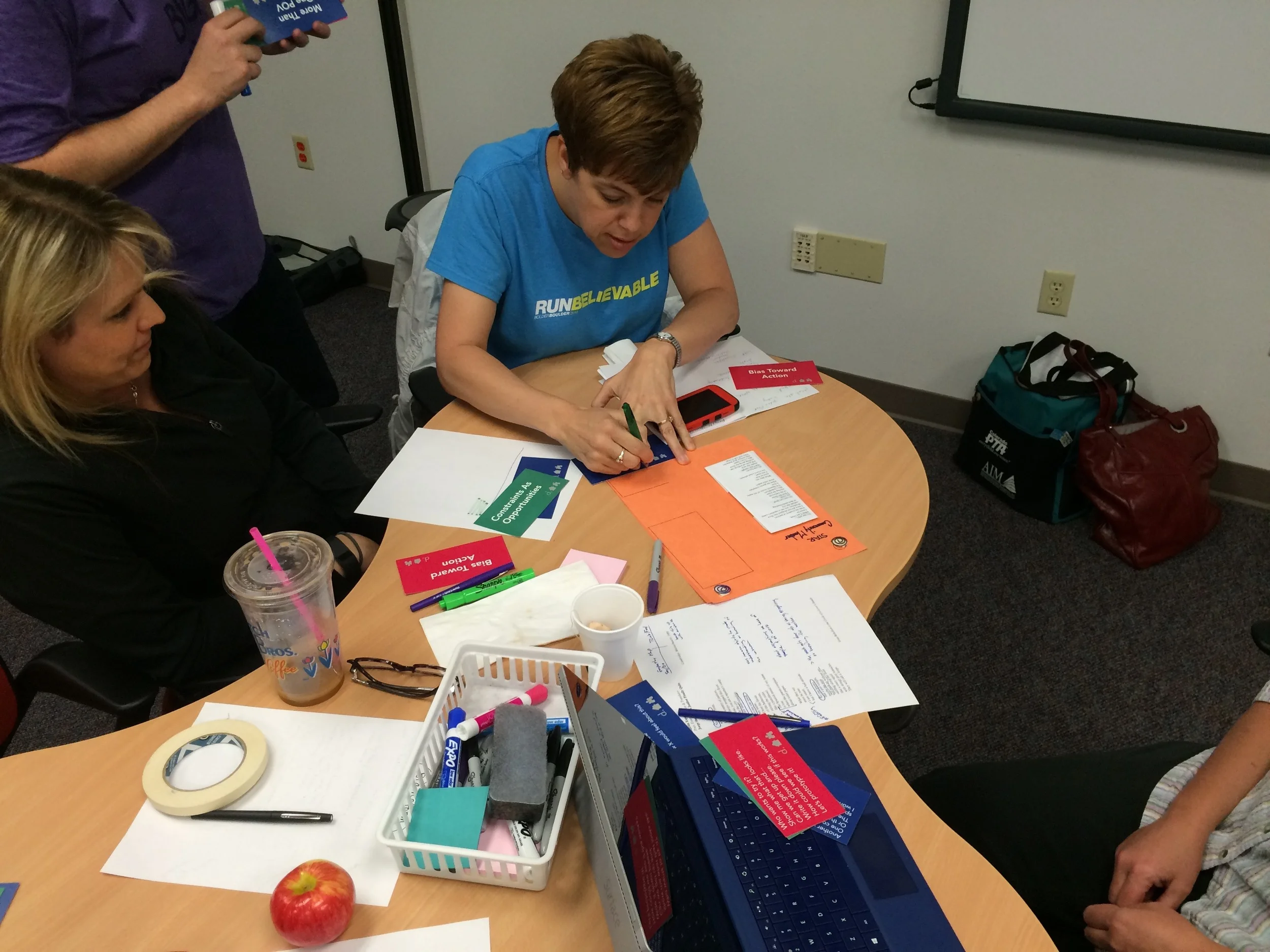

Team members step into the shoes of 6th graders and discuss what is important to Jorge the Janior.

For our second exercise, we challenged educators to step into the shoes of students in a middle school literacy class and design for a character in a poem. Our educators liked the tangible and concrete nature of designing using empathy and being able to apply the design approach to a specific person (even if it was a character and not someone they knew!). The activity led to a lively discussion of how the educators could use a similar protocol across subject matters and brainstormed ways to apply it to science and math in addition to the literature based example used during the workshop.

Adapt it:

During the Stanford workshop, the teachers were offered a choice between a literacy activity and a STEM activity. One of the challenges we have run into while implementing some of the workshops is that we have a more limited staff than the Stanford Team and have to simplify certain components without additional facilitators. We only offered the literacy activity and did not offer the STEM activity. After running the workshop, this adaptation did not leave us (or the participants) feeling like anything was missing or lost in the adaptation and is a good option if facilitation staff is limited.

Adapt it: At this point in the workshop the Stanford team introduced mindset referees who blew a whistle each time a mindset that helps overcome barriers was recognized: 1) bias towards action, 2) constraints and opportunities, 3) different point of view. With less staff resources and after receiving the feedback from the Stanford team that the referee whistles were a little jarring we adapted this portion as well and had the participants and facilitators note and track when one of the 3 mindsets was used without the referee whistle. We looked for examples of mindsets in action at different points throughout the day to reflect on how we were doing as a group.

Work-it Circuit

Next we moved on to the “Work-it Circuit”. These were small activities designed to demonstrate how Design Thinking can be applied successfully as a complete process or in small sections depending on the available time, needs and goals. The educators were able to participate in several short (25 minute) stations. Each station was a stand-alone activity delving into one component of Design Thinking. For example: at one station the group was given a word that has an abstract meaning like “imagine” or “justice”. They were then challenged to make a representation of the word out of play dough, come up with other similar words that describe the original word, and look at the differences of people’s perceptions of the same word.

Adapt it:

The Stanford team offered their participants 2 sets of 3 stations (participants chose 2 activities in each round, participating in a total of 4). With more limited staff we only offered 1 set of 3 (and participants chose 2 of the 3 activities to rotate through). The participants found these stations to be really valuable and offering fewer options did not seem to detract from the value. This is a great option if you have limited staff facilitating the workshop.

Formula for Success

Ready, Set, Go!

Because of the many moving parts in this workshop, our group of facilitators met ahead of time to do extra training and to prepare for the breakout sessions; this was very valuable and kept the workshop running smoothly. Another factor that led to the success of this workshop was that one of our facilitators attended the Stanford workshop before facilitating this one. For the previous workshops, she had not attended the Stanford workshops in person. Having attended the workshop made it much easier to apply and understand the “why” behind each exercise and allowed her to both understand and pass on some of the subtleties that may be missed if only prepping from the workshop materials.

Re-energize!

All of the workshops have provided different experiences and valuable skills. However, the concrete applications of Design Thinking and the process of developing explicit tools in this workshop energized the participants. There were a lot of reflections on the challenges educators face at their schools and valuable discussions about how to break through the barriers these challenges create.